Case Note: Director of Public Prosecutions v Morley [2020] VSCA 313

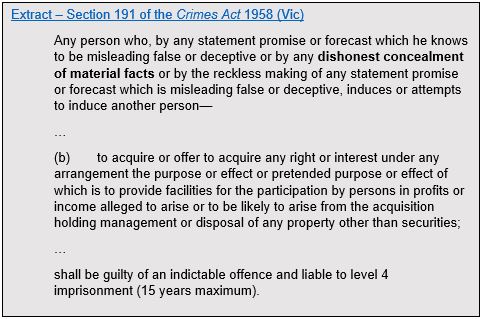

In regards to Section 191 of the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic)

In criminal proceedings where an accused is charged with fraudulently inducing persons to invest money by concealing material facts, the prosecution must prove that the accused acted dishonestly. A recent decision of the Victorian Court of Appeal in Director of Public Prosecutions v Morley confirms that the prosecution is not required to prove that the accused realised that the conduct was dishonest. Instead, a jury must be satisfied that the accused’s conduct was dishonest by reference to the ‘standards of ordinary, decent people’.

Background[1]

Zac and Tim Morley (pseudonyms) are brothers and farmers. At the time of a hearing before the Court of Appeal, the pair were charged and preparing for trial in the County Court for fraudulently inducing a retired couple to invest $395,000 during 2009 – 2010. The investment was supposedly for the purpose of buying 26,335 goats at $15 per head that would be fattened and then sold for a profit. However, the prosecution alleges that, at the time of the agreement with the investors, the brothers and their goat farming business were in a “parlous financial position” and were in breach of another acquisition agreement with a Malaysian company. On this basis, the prosecution alleges that the funds were not used for the agreed purpose and that the brothers either made a false promise to the investors or dishonestly concealed material facts as to their true financial position.

It is an offence under the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) to fraudulently induce a person to invest money, punishable by a maximum of 15 years imprisonment.

Defining Dishonesty

The accused and the prosecution accepted that dishonesty was a core element of the charges, but the parties could not agree on the legal test. The trial judge made a ruling in favour of the accused which the Crown appealed to the Court of Appeal. The issue before the Court of Appeal — constituted by President Maxwell and Justices of Appeal Priest and Kay — was “the test to be applied by the jury in deciding whether any concealment of material information was dishonest.”[2]

The Court of Appeal summarised the position of the parties in the following way:

The prosecution submits, as it did before the [trial] judge, that the word ‘dishonest’ is used in s 191(1) in its ordinary sense, such that the jury should be directed that the question of dishonesty ‘is to be decided by the standards of ordinary, decent people’. The defence submission, by contrast, is that the jury would also need to be satisfied that the relevant respondent knew that his conduct was dishonest according to the standards of ordinary people.[3]

This was not a unique dispute. Adopting High Court and Victorian precedents over a conflicting Western Australian decision, the Court of Appeal adopted the prosecution’s formulation and overturned the trial judge’s earlier ruling.

Accordingly, ‘dishonesty’ is determined objectively. While the prosecution must prove amongst other things that the accused knew of relevant facts, appreciated their materiality to the investor, and deliberately concealed material facts, there is no requirement to prove that the accused had a subjective awareness of their dishonesty.

Key takeaways

- If an accused is charged with fraudulently inducing persons to invest money by concealing material facts, the prosecution must prove amongst other things that the accused: (i) knew the relevant facts; (ii) appreciate their materiality to the investor’s decision to invest money; (iii) deliberately concealed those material facts; and (iv) concealing those material facts was dishonest.

- A jury will determine whether ‘dishonesty’ has been established on the facts by reference to ‘the standards of ordinary, decent people’.

- A person may have acted dishonestly — judged by ‘the standards of ordinary, decent people’ — without realising that their actions were dishonest by those standards.

- Although this is a criminal case, investors that are victims of fraud may also have grounds to bring civil action which may be a preferable course of action to reporting fraud to police for criminal prosecution.

Note: This article is for information purposes only and is not legal advice. If you wish to obtain advice from a qualified fraud barrister about a particular matter, please contact Duxton Hill. We are a Specialised Fraud Law Firm in Melbourne Specialising in Fraud Law & investigations.

[1] Facts summarised from Morley (a pseudonym) v The Queen [2020] VSCA 180 and DPP v Morley (a pseudonym) [2020] VSCA 313.

[2] DPP v Morley (a pseudonym) [2020] VSCA 313., [4].

[3] DPP v Morley (a pseudonym) [2020] VSCA 313., [4].

Recent Comments